Welcome to my very first Victorian true crime post!

I chose a topic close to my heart because it’s related to prejudice against the Irish in the 1800s. I write about that terrible time for the Irish in my historical fantasy series Grimoire Society of Dark Acts. In the series, we meet a few Irish characters who are quite different. Some escaped Ireland due to the Great Famine, and while one is doing well for himself, others are in gangs due to strong anti-Irish sentiment and “No Irish Need Apply” job refusal. Another character, wealthy and with fine manners and social graces, has renamed herself and pretends to have a different heritage altogether to save herself from violent bigotry. As a result, she’s accepted into high society without question.

You’re about to read the true story of Dominic Daley and James Halligan, two Irish immigrants who came to the US to escape British oppression and make better lives for themselves.

Without further ado, please read on.

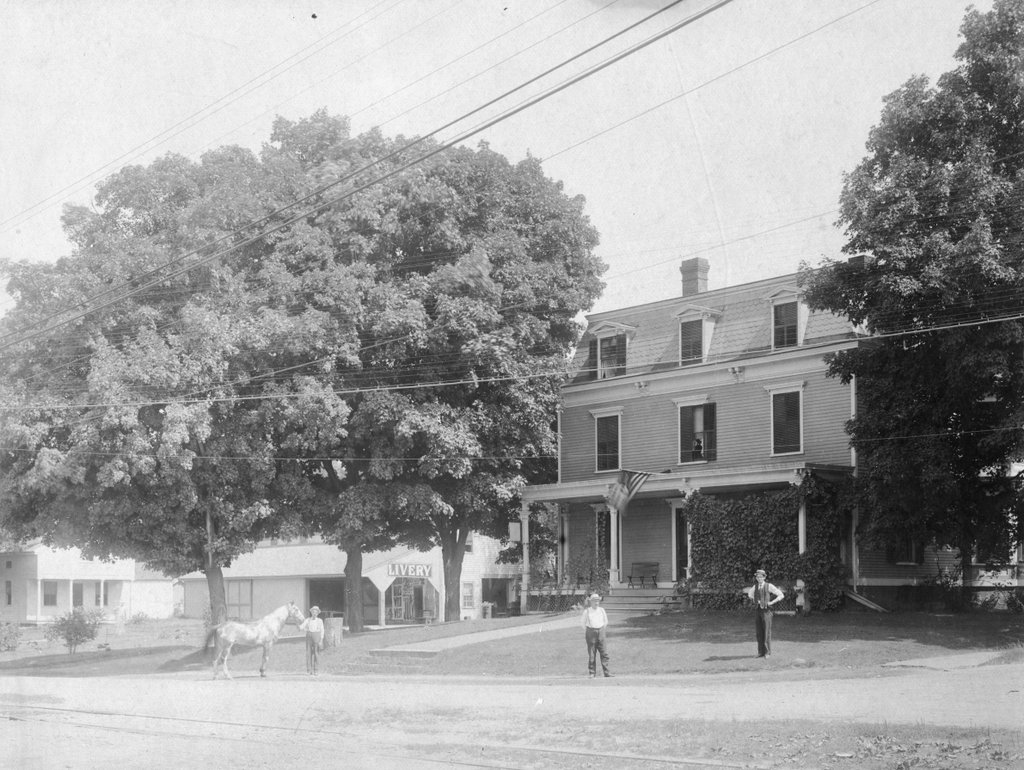

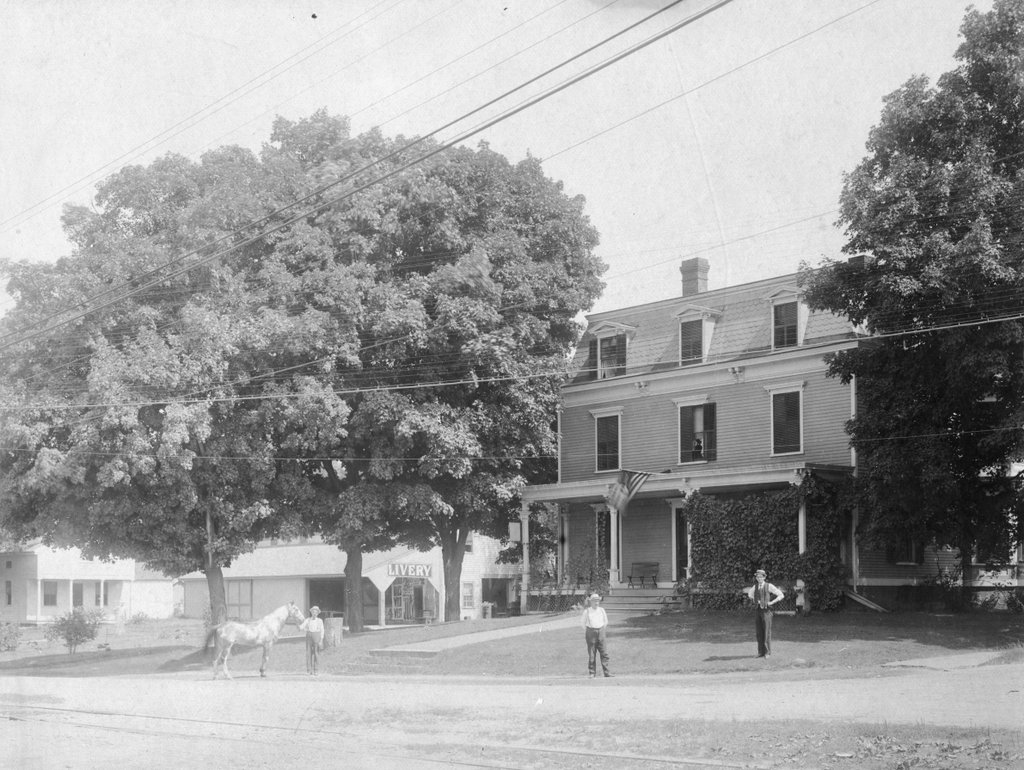

November 5, 1805. Wilbraham, Massachusetts.

A dead body was discovered in the Chicopee River by a local man, and papers in the dead man’s horse’s saddlebags identified him as young farmer Marcus Lyon.

He’d been shot, and his head had been brutally bludgeoned. Two pistols were discovered at the scene.

A 13-year-old boy named Laertes Fuller and a few men claimed to have seen two big men, “strangers”, walking on the turnpike in the general vicinity, supposedly headed toward New York. Laertes alone said he’d seen them on the road, lost sight of them, then fifteen minutes later he saw them on the road again with a horse. Search parties from Massachusetts, New York, and Connecticut tried to find the culprit, regardless of this vague description.

The Arrest.

A search party came upon Irishmen Dominic Daley and James Halligan in New York, wearing rough clothes and brogues, and the group was immediately suspicious. Daley and Halligan were more than willing to be searched and admitted they had walked down that road, but constables arrested them and took them to prison despite finding no evidence and nothing to confirm the search party’s suspicions. A $500 reward was given to the person who turned them in.

It was quickly decided, for reasons still unknown to this day, that Daley had done the killing while Halligan had aided, abetted, and “encouraged.”

Laertes Fuller was called to the jail to see if he could identify them as the men he saw near the murder site, and he confirmed they were the men he had seen.

The Trial.

No one was allowed to visit the two men in prison, not even their families, save for the special prosector in April of 1806. That was also when their official charge of murder was filed, and they plead not guilty at once.

While the prosecution had been preparing their case for 5 months—November 1805 through April 1806—the accused were allowed a whole 48 hours to prepare their defense. They were assigned lawyers who had very little experience to begin with, but most importantly, they had never worked on a murder trial.

(Is this starting to sound like a setup to you?)

The Supreme Court judge was known not to believe in equal rights for Irish Catholic immigrants, something that ran in his family. The prosecutor was a known anti-Catholic, anti-Irish attorney general, looking to become governor in the upcoming election.

(How about now, does this sound like a fair trial now?)

The trial began at 9 a.m. on April 24, 1806.

Although there had been rumors that there would be loads of evidence linking the Irishmen to the crime, it didn’t turn out that way. There were a whopping 24 people who testified, trying to link the two men to the crime, even though none were eyewitnesses, and the most any of them claimed was that they saw Daley and Halligan on the public road near the murder site, where they had already admitted to walking.

A gun dealer testified that someone who “talked like an Irishman” had bought two pistols from him, but he couldn’t identify Daley or Halligan. The proesecutor added to this that both Daley and Halligan were wearing pants with pockets large enough to fit a pistol, though no gun was found on either of them.

The owner of an inn where the victim, Marcus Lyons, had stayed said that the night before Lyons set out toward New York, he’d shown the innkeeper bank notes, two of which looked like ones Daley had on him when arrested.

Ultimately, the judge asked the jury to disregard both the statements about the guns and the money as “circumstances too remote to bear upon the present case.”

Young Laertes Fuller testified with his story of having seen them on the road, then seeing them reappear 15 minutes later with a horse. When asked by the defense whether he’d heard a gunshot, he said no.

No physical evidence was produced against either Daley or Halligan.

At that time in history, defendants were not allowed to take the stand (this changed in 1866), so all they could do was watch their trial unfold.

The Defense.

When it was time for the defendants’ inexperienced lawyers to argue on their behalf, they pointed out the prosecutor’s lack of evidence and the prejudice involved in the case.

Lawyer Francis Blake was the one to make the defense’s speech.

Blake said powerfully in his closing argument:

“Pronounce then a verdict against them! Hold out an awful warning of the wretched fugitives from that oppressed and persecuted nation! Tell them that […] the name of an Irishman is, among us, another name for a robber and an assassin; that every man’s hand is lifted against him; that when a crime of unexampled atrocity is perpetuated among us, we look for an Irishman…and that the moment he is accused, he is presumed to be guilty.”

The trial took only one day, and the verdict came back within minutes: guilty. The two men were to be hanged shortly thereafter.

The Aftermath of the Trial.

Daley’s mother begged the governor to pardon her son and his friend since there was no actual evidence tying them to the crime, and she cited prejudice as the only driving factor in their guilty verdict.

Her plea was denied.

Having nowhere else to turn, Daley and Halligan wrote to Catholic priest Father Jean Lefebvre de Cheverus, asking him to come to them. At least he could minister to them.

The innkeeper in the area refused to house Father Cheverus because he was Catholic. Nobody would take him in, so he stayed at the jail until one person finally risked their reputation to allow him a bed in their home. That man suffered reprisals from the town.

Father Cheverus visited Daley and Halligan every single day until they were to be hanged, giving them communion and hearing their confessions. The only thing he shared from their private words was that they professed their innocence up to the end.

The Hanging.

On the day when Daley and Halligan were to be hanged, Father Cheverus addressed the unusually enormous crowd that had gathered to watch, despite Protestant clergy trying hard to stop him. He openly admonished the crowd for their open interest in watching two innocent men die, and he said to them, “Whosoever hateth his brother is a murderer.” Turning specifically to the many women present, he said, “I blush for you. Your eyes are full of murder.”

60% of Northampton came to watch the hanging, but the total number in attendance was 15,000, a staggering amount of people, among them, men, women, and children.

Dominic Daley and James Halligan were hanged that day, their bodies set to be “dissected and anatomized.” Ironically, a hospital would later be built on the site where they were hanged.

The Eventual Confession.

In 1879, on his deathbed, a man in West Massachusetts reportedly admitted to murdering Marcus Lyon.

Guess who it was?

Laertes Fuller’s uncle.

Modern Remembrances.

Writer Jim Curran wrote the award-winning play “They’re Irish! They’re Catholic!! They’re Guilty!!!” based on the trial’s original 1806 transcript, helping to win posthumous pardons for Daley and Halligan. On St. Patrick’s Day in 1984, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis exonerated them both.

In 2004, author Michael C. White wrote a fictionalized account of the trial and hanging called The Garden of Martyrs.

The two Irishmen are still remembered to this day on the anniversary of their deaths by the local Irish community, with commemoration ceremonies complete with speeches by important groups and people.

Sources:

- The History of the Boston Irish: Little-Known Stories from Ireland’s “Next Parish Over”, Stevens, Peter F. The History Press. 2008.

- “Dailey & Halligan.” Historic Northampton Museum & Education Center. http://historic-northampton.org/virtual_tours/Markers/Markerpanels/daleyandhalligan.html

- “Digital Collections: ‘Proceedings on the Trial of the Dominic Daley and James Halligan.’

American Centuries. http://americancenturies.mass.edu/collection/itempage.jsp?itemid=17971 - “Sons of Ireland commemorate 1806 hangings of Domenic Daley, James Halligan for murder.” Mass Live. https://www.masslive.com/news/2015/06/sons_of_ireland_commemorate_th.html

- “Dominic Daley and James Halligan Trial: 1806.” Encyclopedia.com. https://www.encyclopedia.com/law/law-magazines/dominic-daley-and-james-halligan-trial-1806